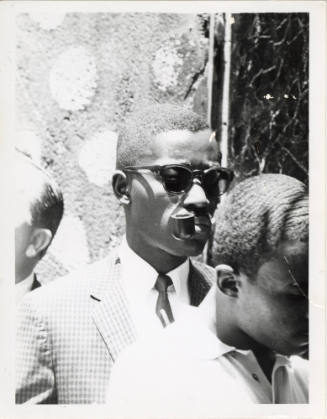

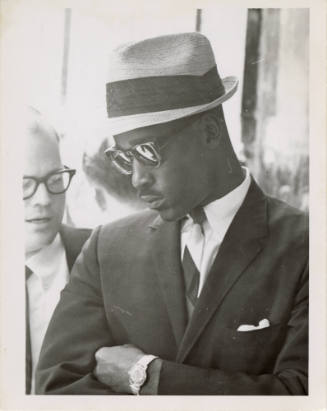

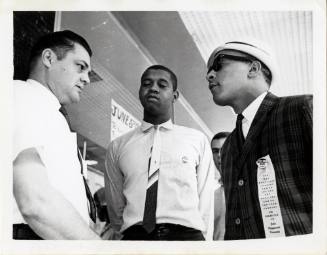

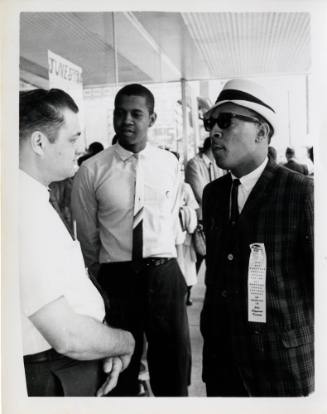

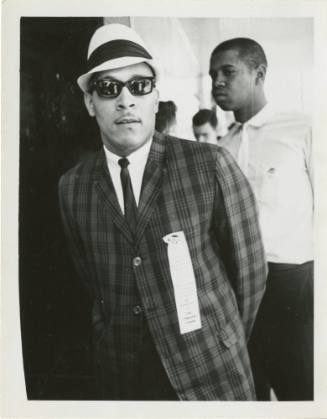

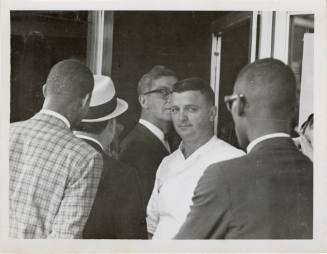

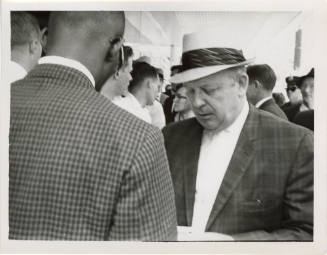

Photograph of people at a 1964 civil rights protest in Dallas

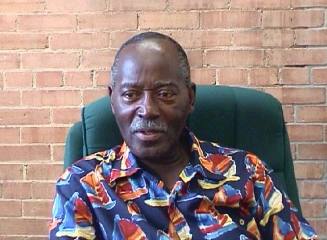

The Rev. Earl Edward Allen, born in Houston in 1933, moved to Dallas to attend Perkins School of Theology at Southern Methodist University in 1960. By the time of the Kennedy assassination, he was pastor of the Highland Hills Methodist Church in Dallas, and he also became active with the local chapter of CORE, the Congress of Racial Equality.

His civil rights activism began at SMU. In a 2006 oral history with The Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza, the Rev. Allen remarked, "Prior to [the Piccadilly demonstration], we had also been involved in civil rights activities as a student at SMU. There were a number of institutions or places of business...that were not available to blacks at that time. I was one of the few blacks at that school at the time, and I lived on campus.... I was involved in campus life and so on, and discovered that there was a drugstore...and several other places right across the street from the university that were segregated.... So we began activities on the campus that were designed to eliminate that situation, which we did successfully."

In addition to this 2006 one-on-one videotaped interview, the Rev. Allen joined with Piccadilly protest co-organizer Clarence Broadnax for a program at the Museum in 2008. This can be viewed in its entirety on the Museum's YouTube Channel: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c-d7GD_P-Nw. The Rev. Allen passed away in 2020. - Stephen Fagin, Curator

One of the most prominent and sustained civil rights protests in Dallas history occurred at the downtown Piccadilly Cafeteria at 1503 Commerce Street. Beginning May 30, 1964, activists interested in desegregating the popular cafeteria peacefully protested at the site for twenty-eight consecutive days. During that time, seventeen demonstrators were arrested for “disturbing the peace,” ranging from a sixteen-year-old high school student to a thirty-seven-year-old housewife. The protest brought Dallas national media attention, with articles appearing in publications such as the New York Times, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal and Los Angeles Times. Local newspaper, The Dallas Morning News, ran approximately twenty-five stories on the demonstration over the course of one month.

Although initiated by the actions of Dallas resident Clarence Broadnax, who was arrested and allegedly threatened by Dallas police officers after refusing to leave the cafeteria in May 1964, the actual demonstration was principally organized by Dallas minister Earl Allen, then pastor of Highland Hills Methodist Church and a local leader with the Congress of Racial Equality. This CORE demonstration in Dallas followed the same basic rules as other restaurant protests throughout the south at that time. Each day, especially during the weekday lunch rush, peaceful demonstrators would join the line outside and wait to be refused service at the door before going to the back of the line and trying again. This resulted in a noticeable slowdown in business, causing the cafeteria to lose money—one of the only ways that civil rights organizations could effectively change long-standing racist segregation policies. Other protestors supported those in line by chanting, singing or holding up signs and marching up and down Commerce Street to attract attention.

While crowds of up to 150 people would sometimes gather to watch the demonstration in action, the situation also attracted groups of white segregationists, who heckled the demonstrators and brandished Confederate battle flags in counter protest. While this elevated the threat of violence—and Dallas judge Dee Brown Walker once called the protest “an explosive situation”—no violent altercations occurred during the twenty-eight-day demonstration. Piccadilly Cafeteria chain founder and president T.H. Hamilton told The Dallas Morning News one week into the demonstration: “We are trying to go along as fast as we can, but we do not like being pushed.” Rather than immediately change its “whites only” serving policy, the cafeteria attempted to solve the crisis through legal action. For the duration of the protest, lawyers on both sides of the argument were in and out of Dallas courtrooms. Despite a restraining order that forced protestors fifty feet away from the entrance, the pattern of slowing down lunch traffic continued.

After nearly a month of persistent daily protests, the demonstration finally reached a conclusion, through a very unlikely source. A forty-two-year-old white aeronautics engineer in Dallas stepped forward when his two teenage sons were arrested for participating in the demonstration. He took it upon himself to organize a private meeting with both parties, and a resolution was reached. The result: Piccadilly Cafeteria would immediately begin serving African Americans as soon as President Lyndon Johnson signed the upcoming civil rights legislation. The daily protests would cease immediately, and all charges against those who had been arrested during the protest would be dropped. Two and half hours after President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act on July 2, 1964, an African American minister was served at the cafeteria without incident. When questioned by reporters afterwards, the Rev. John Bethel said simply, “Everyone was polite, and the food was good.” That month, Time magazine reported: “Throughout the South, from Charleston to Dallas, from Memphis to Tallahassee, segregation walls that had stood for several generations began to tumble in the first full week under the new civil rights law.”

After twenty-two years of operation in downtown Dallas, the Piccadilly Cafeteria on Commerce Street closed in October 1977. The southeastern cafeteria chain, founded in 1944, remains in business with around 30 locations still in operation as of 2021. – Stephen Fagin, Curator